Adventures In Cool Music: GRANT GREEN

SOUL-JAZZ & GRANT GREEN

SOUL-JAZZ & GRANT GREEN

During the turbulent and hipper-than-thou late 1960's, perhaps no musical genre was considered more hopelessly 'old-school' than Soul Jazz. Based largely on the standard I-IV-V blues chord progression and driven by the traditional gospel keyboard instrument, the Hammond B-3 organ, soul-jazz was infrequently heard on rock, pop, or even most jazz radio. The local ghetto bar's 45 jukebox was the true home of the music and live appearances were usually relegated to small, smoky joints buried deep within the inner cities of the Midwest and Northeast in shady dives where working-class folks gathered to drink and unwind after a long day. This was straight-forward music played for everyday people and performed by journeyman musicians from around the way -- effete artiste-types needed not apply. Although plenty of soul-jazzers were recorded by big-time record labels like Prestige and Blue Note, many of the albums sold weakly during a time when an exaggerated premium was placed on avant-garde experimentation by theorist jazz critics and poindexter neo-revolutionaries enamored by the radical socio-political statement of the totally free "New Thing" music.

In this purist context, soul-jazz's R&B backbeat and groove-driven funk was dismissed as a watery hodgepodge of boogaloo melodies, classic gospel tension & release arrangements, and disposable rock n' roll rhythms. Jazz snobs criticized the music as a trite throwback to an era when saxophonists prostrated themselves honking the blues or walking the bar for tips instead of engaging in neo-mystical, rarefied quests for higher musical consciousness or -- at least -- dutifully reviving Louis Armstrong riffs. And unlike their more fortunate musical contemporaries who could occasionally hold jazz concerts in theater halls or upscale clubs, the soul-jazz musician's lot was to work nightly in sketchy roadhouses or sweat-soaked bars offering dim, tiny stages and the job description was bone simple: provide hot dance music for the rowdy masses. The soul-jazz sound had few pretensions and no room for precious soul-searching solos or ambiguous 40-minute modal improvisations. The almighty GROOVE was where it was at and if people weren't shaking their ass and drinking themselves cross-eyed to the music, baby, you better believe those bread and butter gigs would have evaporated like wet dew in the hot morning sun.

Perhaps one difficulty soul-jazz music encountered in its attempt to break through to the general jazz-buying public was the overwhelming number of artists who were active within the genre. There was no one singular standout talent, like a John Coltrane or an Ornette Coleman in avant-garde jazz, who could spearhead the soul-jazz movement and become a focal point for larger audiences; in other words, a "star" who could draw critical media hype. Instead, there were literally hundreds (thousands?) of underground 'funky jazz' artists who released tons of albums during the heyday between 1964-1974 and who could typically be found gigging at strip joints, hotel bars, airport lounges, neighborhood weddings, soul food restaurants -- or anyplace else where the stage was big enough to fit the mammoth organ and hold a drum kit. Many avatars of soul-jazz began their careers as more mainstream jazz musicians or as sidemen employed by other bands, but lots of superb players rarely strayed from the gutbucket, ghetto-bred funk-soul-jazz format, hence basically ensuring their total anonymity with the usual (read: white) jazz fan. Nearly all their best and now most intensely sought-after records largely disappeared from view upon issue and some performers never released records in other more well-regarded fields of music.

Therefore, massively gifted musicians like Charles Kynard, Eddie Senay, Jimmy McGriff, Charles Earland, Johnny "Hammond" Smith, Don Patterson, Rusty Bryant, Melvin Sparks, Groove Holmes, Boogaloo Joe Jones, Freddie McCoy, Reuben Wilson, Leon Spencer, Billy Butler, Eddie "Funk" Fisher, Bernard "Pretty" Purdie, Freddie Roach, Brother Jack McDuff, Sonny Phillips, Bill Mason and dozens more became obscure blips on the radar screen of jazz history despite their sublime talents. Other more well-known musicians who arguably created their best work playing funky soul-jazz include Cannonball Adderley, Herbie Hancock, Grover Washington, Freddie Hubbard, Donald Byrd, Jimmy Smith, Lou Donaldson, Eddie Harris, Yusef Lateef and others. Even MOR specialist Bob James, who wrote the famous Fender Rhodes-driven "Theme from Taxi" for television in 1975 had made a couple of earlier LPs on the CTI label bursting with fierce soul-jazz sounds (not to mention his infamous avant session for ESP Records in late '60s!). Of course, the fact that much soul-jazz repertoire consisted of heavily funked-up versions of popular R&B and rock hits did little to advance its credibility with jazz purists. This despite the fact that jazz music has always maintained a long tradition of improvising on hit pop songs of the day and re-interpreting them in a 'jazz' vein, thereby meeting the typical audience desire to hear something they know. Interestingly, the funky soul-jazz sound quickly spread into the neo-Latin music scene emerging from New York City's Cuban and Puerto Rican neighborhoods in the late 1960s/early '70s, resulting in a raw and groove-heavy hybrid of Salsa music that was very danceable and which remains hotly desired by record collectors on small regional labels like Panart, Tico, Coco, Vaya, and Fania.

One artist who may perhaps be considered definitive of the whole soul-jazz movement -- if such a thing even exists -- is St.Louis-born guitarist Grant Green who recorded a boatload of records for the Delmark, Blue Note, Verve, Kudu, and Versatile labels as a leader from around 1960 to 1977, while also appearing on literally hundreds of albums by other performers. His in-demand first-call status among recording musicians made him one of the few jazz artists whose ubiquitous studio work over a period of fifteen years can be accurately said to portray the sound of an entire musical genre. Guitarists like Wes Montgomery and George Benson may certainly have received more widespread acclaim, but it was Green's intense, single-note style full of lyrical melodic phrases, sleek turnarounds and oddball staccato rhythmic figures that really birthed the instrumental palette of modern jazz-funk guitar. Grant's liquid playing fused pure gospel blues feeling with dirty street funk, producing an irresistibly groovy yet deep signature sound that remains clearly unique and thoroughly astonishing even forty years later. His lasting influence on every single jazz, funk or soul guitarist after him -- especially folks like George Benson, Melvin Sparks, John Scofield, and Charlie Hunter -- is certainly undeniable.

One artist who may perhaps be considered definitive of the whole soul-jazz movement -- if such a thing even exists -- is St.Louis-born guitarist Grant Green who recorded a boatload of records for the Delmark, Blue Note, Verve, Kudu, and Versatile labels as a leader from around 1960 to 1977, while also appearing on literally hundreds of albums by other performers. His in-demand first-call status among recording musicians made him one of the few jazz artists whose ubiquitous studio work over a period of fifteen years can be accurately said to portray the sound of an entire musical genre. Guitarists like Wes Montgomery and George Benson may certainly have received more widespread acclaim, but it was Green's intense, single-note style full of lyrical melodic phrases, sleek turnarounds and oddball staccato rhythmic figures that really birthed the instrumental palette of modern jazz-funk guitar. Grant's liquid playing fused pure gospel blues feeling with dirty street funk, producing an irresistibly groovy yet deep signature sound that remains clearly unique and thoroughly astonishing even forty years later. His lasting influence on every single jazz, funk or soul guitarist after him -- especially folks like George Benson, Melvin Sparks, John Scofield, and Charlie Hunter -- is certainly undeniable.

A completely un-schooled, self-taught player but nevertheless a consummate musician, Green had a country-bumpkin demeanor that belied the most fluid technique in jazz guitar history save for maybe Django Reinhardt or Pat Martino. His elegant, warm tone never lost its supple edge whether he was playing lightning-fast bebop flurries or one-chord, deep-groove nastiness and his three dozen or so records as leader vary in approach from Charlie Christian-inspired hard-bop to black-gospel standards to blaxploitation soundtracks to Sly Stone, Meters and James Brown covers; if one could possibly fit a guitar onto the recording, Grant always tore it up without fail. Although his most critically celebrated work came during the early 'hard-bop' part of his career, Grant Green's later-period funky albums have finally been receiving some major recognition from hip record collectors, sample-hounds and jazz cognoscenti worldwide.

Grant began his steady evolution from straight-up jazz into a more funky approach with his sole release on Verve Records , the rather appropriately titled 'His Majesty King Funk,' released in 1965. Along with Hammond B-3 mystic Larry Young, workhorse drummer Ben Dixon and bop saxophonist Harold Vick, Green lays down thick textures and stingingly clean leads that defy the boundaries of what was typical jazz guitar at the time. Buoyed by the just-emerging youth culture movement, he applied a loose, swinging yet restrained approach to classics like "The Cantaloupe Woman" and "Get Out Of My Life, Woman", both soul-jazz standards that went on to be covered hundreds of times by many artists. The creeping rock influence on Grant's playing was slowly becoming increasingly evident and his famous quote: "Jazz, R&B, soul, rocknroll -- it's all just the BLUES, man!" truly clarified where he was coming from. Larry Young (aka Khalid Yahsin) -- Grant's organist on this album and several others -- had a massively swirling B-3 organ sound with slightly psychedelic vibe which he further expanded on his own recordings, many of which were so far ahead of their time as to sound a bit spaced-out even today. Young was considered by some to be the "Coltrane Of The Organ", although his Hammond keyboard tone always retained a tough edge born on the mean streets of Newark's ghetto no matter how 'outside' his playing became. Young, who infamously appeared uncredited on Miles Davis breakthrough 'Bitches Brew' album and who was an integral member of the band Lifetime along with John McLaughlin, Jack Bruce and Tony Williams in the early '70s, died of liver disease & pneumonia in 1978 after his last couple of records found him addressing fusion/dance-funk in his own wholly inimitable way. Watch for a much more in-depth analysis of Larry Young LPs on subsequent Adventures in Cool Music.

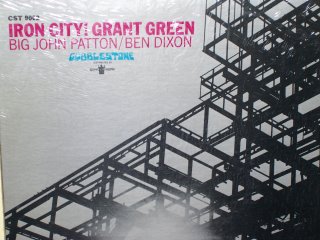

Grant's next release, the rare 1967 album 'Iron City!', really showed where he would ultimately wind up: smokin' guitar playing surrounded by unique arrangements full of fire and brimstone. Powered by infectious vamps and long lead lines, Green explodes on solo after solo as Big John Patton's (another criminally under-heralded musician) B-3 organ majestically churns in the background and stalwart Dixon drums his ass off. Everything's played in something approaching an up-tempo frenzy on this album -- except for the ballad stunner "Motherless Child" -- and the non-stop, crushing backbeat throughout 'Iron City!' points the way to the fiery funkitude that would follow at the turn of the decade. Each track builds up a hot groove as Green exploits every chord change for maximum intensity, the standouts being the unchained title track, the Brazilian head-nodder "Samba d'Orpheus" and the proto-soul classic "High Heel Sneakers." The lean, take-no-prisoners trio setting on this album was one of the guitarist's best showcases to date for his fast-developing funky virtuosity and remains a personal favorite; It's one of those records you never get tired of no matter how often it's played.

Grant's next release, the rare 1967 album 'Iron City!', really showed where he would ultimately wind up: smokin' guitar playing surrounded by unique arrangements full of fire and brimstone. Powered by infectious vamps and long lead lines, Green explodes on solo after solo as Big John Patton's (another criminally under-heralded musician) B-3 organ majestically churns in the background and stalwart Dixon drums his ass off. Everything's played in something approaching an up-tempo frenzy on this album -- except for the ballad stunner "Motherless Child" -- and the non-stop, crushing backbeat throughout 'Iron City!' points the way to the fiery funkitude that would follow at the turn of the decade. Each track builds up a hot groove as Green exploits every chord change for maximum intensity, the standouts being the unchained title track, the Brazilian head-nodder "Samba d'Orpheus" and the proto-soul classic "High Heel Sneakers." The lean, take-no-prisoners trio setting on this album was one of the guitarist's best showcases to date for his fast-developing funky virtuosity and remains a personal favorite; It's one of those records you never get tired of no matter how often it's played.

After serving a prison sentence for drug possession in the late 1960's, Green eventually returned to recording reborn as a Muslim with fresh ideas about music and about the difficult life led by inner-city people, inspiring him to deliver an amazing run of what may be the funkiest records ever made by a so-called jazz guitar player. The double-LP set 'Live at the Lighthouse' and the also in-concert 'Alive' -- recorded at Newark's infamous drug dealer hang-out The Cliche' Lounge -- showcase Green's  burgeoning affinity for James Brown, early Kool & the Gang, and spiraling one-chord extended jams. These late-night live recordings were an anomaly for the steadfastly formulaic Blue Note Records, but Green insisted that this was where his new sound could really open up and shine -- not in some sterile New York studio at 2 in the afternoon. His playing on these LPs is both free-flowing and incredibly tightly wound, an odd dichotomy that few other musicians could ever manage. His guitar went toe-to-toe with electric piano, vibes and an army of percussionists for the first time and the resulting music was revelatory in its force and unshakeable grooviness. On the 'Alive' album, Green takes the Don Covay/Steve Cropper R&B classic "Sookie, Sookie" into some hardcore jazz-funk terrain, teasing out line after smoldering line from his Gibson hollow-body guitar, periodically laying out for the Fender Rhodes and conga breaks that now peppered his sound. His signature track became "Down Here On The Ground," an affecting mid-tempo ballad he used as a tribute to Wes Montgomery, a guitarist he was often compared to but actually sounded nothing like. The emotion-charged performances on these LPs were a direct result of the atmospheric club settings, fueled by the feeling of brotherhood and close support between band and audience.

burgeoning affinity for James Brown, early Kool & the Gang, and spiraling one-chord extended jams. These late-night live recordings were an anomaly for the steadfastly formulaic Blue Note Records, but Green insisted that this was where his new sound could really open up and shine -- not in some sterile New York studio at 2 in the afternoon. His playing on these LPs is both free-flowing and incredibly tightly wound, an odd dichotomy that few other musicians could ever manage. His guitar went toe-to-toe with electric piano, vibes and an army of percussionists for the first time and the resulting music was revelatory in its force and unshakeable grooviness. On the 'Alive' album, Green takes the Don Covay/Steve Cropper R&B classic "Sookie, Sookie" into some hardcore jazz-funk terrain, teasing out line after smoldering line from his Gibson hollow-body guitar, periodically laying out for the Fender Rhodes and conga breaks that now peppered his sound. His signature track became "Down Here On The Ground," an affecting mid-tempo ballad he used as a tribute to Wes Montgomery, a guitarist he was often compared to but actually sounded nothing like. The emotion-charged performances on these LPs were a direct result of the atmospheric club settings, fueled by the feeling of brotherhood and close support between band and audience.

Along with a funky-crazy (and seriously collectable) soundtrack LP for a kitschy Billy Dee Williams 'Black-Power' melodrama called 'The Final Countdown,' Green's early 70's studio work begins to show a man who fully identifies with the struggles of his people as his sound becomes more urban and less obviously "jazz" with every release. The 1970 album 'Green is Beautiful', one of his true masterworks, features hipster versions of James Brown's "Ain't It Funky Now" -- which amazingly out-funks the original (a damn hard feat!) -- and a cool, hypnotic take on The Beatles "A Day in the Life" as re-interpreted for ghetto folks actually living down on the ground. His sly reworking of melodies and rhythms on these cover tunes, however, is nothing if not true jazz as evidenced by the harmonic sophistication and melodic inventiveness he brings to these rather disparate-sounding tracks. 'Green is Beautiful' also contains the hard-swinging original "The Windjammer," a song which was to become a staple of his and many other jazz artists' standard repertoire. His other turn-of-the decade LP classic, 'Carryin' On' from late 1969, has a stunningly deep-funk version of The Meters "Ease Back" and yet another killer James Brown tune, "I Don't Want Nobody to Give Me Nothing (Open Up the Door I'll Get it Myself)," envisioned as 100% pure groove for Green's flexible funk-jazz purposes. He would record other James Brown tracks later in the decade, including "Cold Sweat", and also take on Stevie Wonder, Burt Bacharach, The Carpenters, and Mozart (!) amidst his own superb originals, proof positive that Green never rested on his ballyhooed jazz laurels, unlike nearly every other musician of his generation.

Despite being dismissed as sell-out "commercial" records by narrow-minded, establishment jazzbos, these late-period Grant Green albums broke trail for a whole slew of players who dug the modern sounds of musicians like Jimi Hendrix and Sly & The Family Stone but who were weaned on the classic jazz of an earlier era. By essentially distilling modern jazz guitar down to its rhythmic core and embellishing his own completely unique style atop the hard-edged groove, Green was able to straddle both the jazz and funk worlds effortlessly and create a new musical language that would only grow over time. His working band was always full of up-and-coming young players like sensational keyboardist Neal Creque (writer & co-arranger of many of Green's classics), monster New Orleans drummer Idris Muhammad, and funk organist/session giant Ronnie Foster -- all part of Grant's insistence that his music was completely of today and not some echo of any previous style. His fervent eclecticism foreshadowed the commingling of all musical styles later in the decade (and on into the next century) in a way that no jazz musician had previously approached. The confident musicality, agile ensemble interplay and command of instrumentation has always been the hallmark of old-school jazz musicians, but the willingness to experiment and step outside of convention to reach out to the average non-jazz listener was nothing if not a calculated 'pop' move, a concept that would slowly filter down throughout the jazz world, at times unfortunately resulting in the deadly-dull "fusion" of the mid 1970s.

Green's own life-long alcohol and drug addiction slowly caught up to him as the 1970s progressed and his health seriously faltered in the late 70's after years of constant gigging and merciless self-abuse. Grant died of a massive heart attack in January 1979, penniless and forgotten in most jazz music circles. Thankfully, his god-like status has now been fully restored with Hip-Hop culture rabidly sampling his records in search of the perfect beat and rhythm track. Although much of Grant's work has been officially re-released on CD, his early first-press Blue Note LPs still easily command 3-figure sums on the collectors market. In many minds, Grant Green will always live on safely ensconced as a true genius of jazz guitar without peer.

Labels: Grant Green, guitar, jazz, jazz-funk, LPs

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home